Escaping Elephants & Bears in Trees: the Story of Lincoln Park

Grant Park may be Chicago’s Front Yard, but Lincoln Park is its playground.

Each Thursday, discover an historic Chicago landmark and meet the people who built the Windy City. Includes audio recorded by the amazing Jim Goodrich.

From rogue sea lions, cavorting elephants, and thousands of dead bodies, the story of Lincoln Park is not your typical civic planning affair.

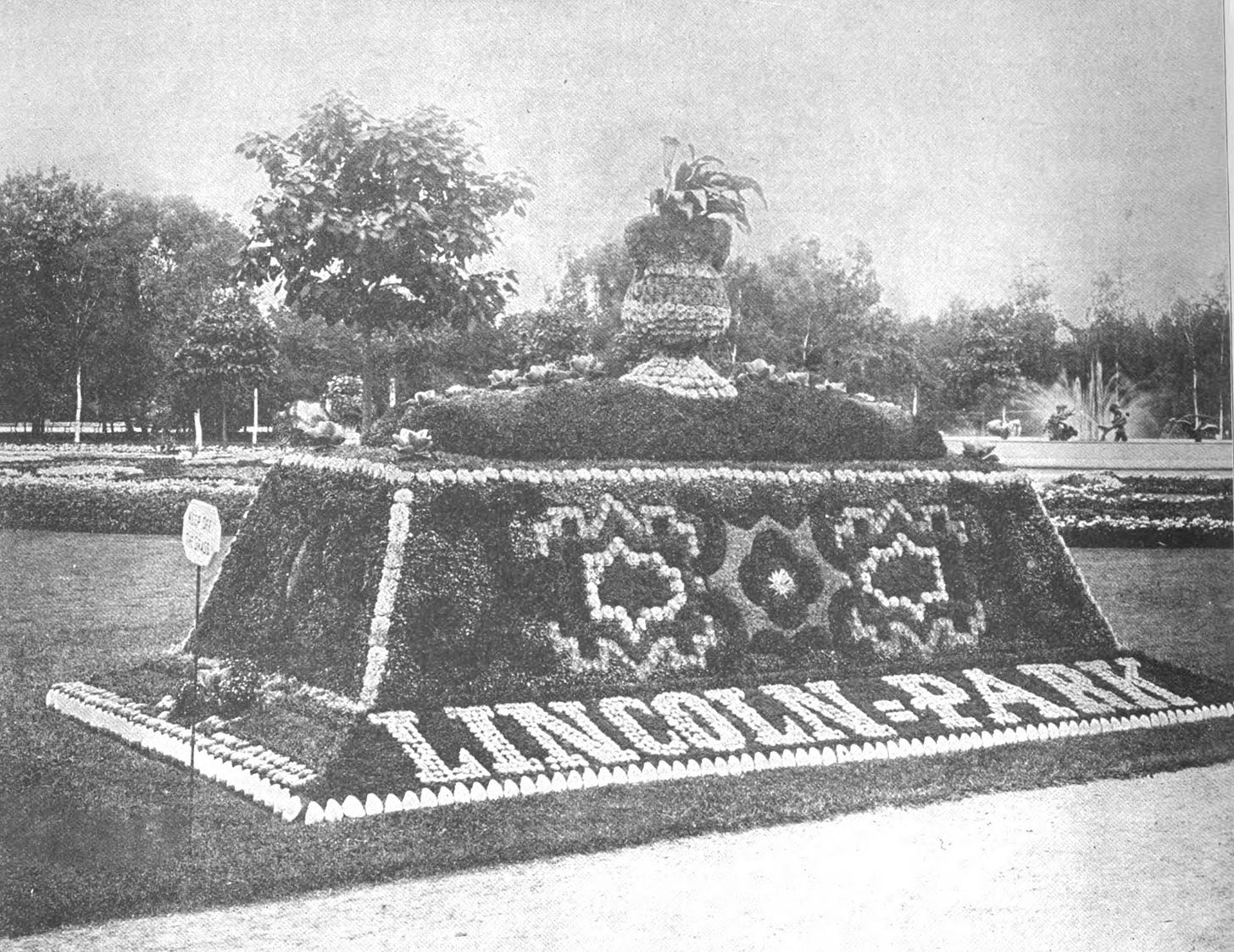

Take a look at a map of Chicago’s north side and you’ll notice a huge swath of green along the lake. It stretches seven miles from Ohio Street to Ardmore Avenue, covering 1,214 acres lined with beaches and filled with gardens, sculptures, museums, thousands of trees, and oodles of sporting facilities. That complicated expanse is Lincoln Park, and it was a long time in the making.

You don’t create a city park of that size by drawing lines on a map and writing: “Insert Park Here.” This public space jumped through a lot of hoops and over a bunch of dead bodies to become what it is today.

Wait—dead bodies? Yep. Thousands of them.

Every city needs cemeteries, and in 1837, the year Chicago incorporated, the Illinois legislature gave the municipality the right to use one of the lots sold by the canal commission for a burial ground. Starting at North Avenue, this location seemed remote enough, and for a little while it was.

The city couldn’t start using this land until they paid for it, and they finally settled their $8,000 fee in 1842. Once Chicago officially acquired the land they began to sell burial plots, complete with deeds. Some people paid, and some showed up with shovels.

The indigent had their own mass grave. The nearly simultaneous opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canal and the introduction of trains in 1848 meant a population boom in a city without health regulations, and cholera invaded. In 1852, the Common Council bought three large tracts of land north of the cemetery to be used for a hospital and a quarantine zone. Fortunately, that particular cholera crisis abated before they needed to use the land for that purpose.

It didn’t take long for the city to grow up and around the cemetery. That meant lots of people lived across the street from lots of graves—shallow graves, filled with lots of diseased deceased. East of the cemetery, swales crowded with poison ivy led toward a wide beach of sand that shifted with the meanderings of the persnickety shore. Then there was the Ten-Mile Ditch. Dug to drain water from Evanston, stagnant pools made it more a swamp than a stream.

Altogether, it was a very unpleasant place. Citizens and physicians raised a hue and cry. They wanted the bodies moved elsewhere, and they wanted a park.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Living Landmarks of Chicago to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.